Šid

The town of Šid is one of the places with earliest records of Jewish habitation in the region of Syrmia. In 1721, only fifteen years after the first written record of the town itself, brothers Adam and David were recorded as traders in petty goods in Šid. Beside the written record, archaeological findings trace Jewish presence in Syrmia all the way to antiquity. In Šid area, signs of Jewish habitation reach as early as the Middle Ages.

By the early 19th century, Jews inhabited virtually all towns in Syrmia. In the period of 1842-1847, four Jewish families were recorded in Šid—Ignac Steiner household, a family of six, Avram Lustig household, a family of three, Jakob Hirth household, a family of ten, and Josif Altwehr household, a family of ten—altogether twenty-nine people. By 1864, Šidian Jews had their own cemetery. A synagogue was established soon after, first in the form of a house that the community rented from the Serbian Orthodox Church, in 1923 moving into a three-room building within the house complex of the Winterstein family. Šidian Jews spoke Yiddish and German, and wrote mainly in the Hebrew alphabet.

The first decades of the 20th century—after the Habsburg monarchy granted Jews civil equality in 1867 and religious equality in 1895—were the years of prosperity for the Jewish community of Šid. Since the town’s foundation and into the interwar period, Serbs made up the majority of Šid’s population, holding in their hands most of the local economy. Jews operated a smaller portion of local businesses and shops, but had a visible presence in the town.

At the eve of the Axis invasion of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in April 1941,

the Jewish community of Šid numbered around ninety people. Immediately after the invasion,

it appears the German occupying forces and local activists of the German National Group were the main

instigators of early anti-Jewish measures in Šid. Croat nationalists grouped under the Ustaša banner at

first instigated measures against local Serbs, whereas both groups persecuted local Roma.

The first anti-Jewish measure in Šid was the confiscation of radio devices from Jewish households.

On April 27, Croat and German authorities introduced compulsory labor for Jews and Serbs,

forcing them to fill in holes in the ground created by bombings during the Axis invasion, as well

as clear and repair roads. Around the same time, a large unit of German army arrived in Šid,

immediately implementing various forms of anti-Jewish persecution. On May 1, 1941, the German

“sonderführer” ordered the formation of new Jewish forced labor squads, tasking them with cleaning

public toilets, floors, railway cars, construction work, and garbage disposal at the town’s railway station;

these tasks were interrupted with daily, public “physical exercises,” during which German guards

forced Jews to prostrate themselves in a nearby muddy ditch, then ordering them to crawl to an adjacent ditch,

which was full of water.

Over time, Jewish forced labor squads received more tasks, such as cleaning the German soldiers’ boots,

and were combined with Serb forced labor squads to clean streets and dispose of the town’s garbage;

Jewish women were also organized into forced labor squads, tasked with washing the German soldiers’ laundry.

In early May 1941, the German “sonderführer” introduced the requirement that every Jew wear a yellow armband

on the left sleeve.

Concurrent with these events, the Ustaša regime and its local representatives introduced multiple

pieces of anti-Jewish legislation, such as public marking of Jews with a yellow armband, later replaced with

a round sign featuring the letter “Ž,” standing for “Židov” (“Jew”), to be worn on the chest.

The regime ruled that Jews must report all their property, prohibited their movement on Sundays and

Catholic holidays, instituted a general curfew for Jews from 8 PM until dawn, forbade Jewish attendance

of leisurely establishments such as coffee houses, restaurants, and cinemas, as well as Jewish attendance

of food markets before 10 AM, the hour after which very little food remained at the stalls. In addition,

most Jews were dismissed from their places of employment.

In the very beginning of Ustaša tenure in power, April-May 1941, the Jewish community

of Šid was ordered to make a “contribution” payment to local Ustaša headquarters.

Šid’s Serb elites were included in this order. Ustaša District commander Josip Šuk tasked

District Clerk Ivan Daražac with collecting the money, giving Daražac a list of Jews and Serbs

who were each to ‘contribute’ specific amounts.

Following “contribution” payments, Šid’s Ustaša authorities assigned “commissars” to

Jewish and Serb shops, a transitional step in transferring Jewish and Serb businesses to

Croat “Aryan” hands. Local Ustašas used “commissar” positions as rewards bestowed to Croats

who already showed their loyalty to the movement, as well as bait for key local Croats to join

the Ustaša project. Like elsewhere in the NDH, the dispossession of the town’s Jewish community

and Serb elites was managed by officials of the Ustaša regime’s State Directorate of Economic

Reconstruction. In Šid, they were Stjepan Milčić and his assistant Josip Ivšić, who used their

positions to siphon much of the property expropriated from Jews and Serbs into their own pockets,

as well as those of other prominent local Ustašas.

In summer 1941, the first Šidian Jew to be deported to Ustaša camps, his face disfigured from beatings, was young leather merchant Petar Stern. Soon after, local Ustašas deported carpenter assistant Miša Han to Jasenovac death camp, allegedly to help construct coffins there. One Sunday in late summer, the Jewish community buried Gerzon Epstein, who had passed away. Despite the municipal permit for the burial, Ustaša authorities were enraged. Upon learning of the burial, regional Ustaša Commander Luka Puljiz, accompanied by the regional Female Ustaša Youth Commander Kaja Senić, arrived in Šid from Vukovar, the regional capital, and interrogated rabbi Herman Spiegel and representatives of the Jewish community council Emil Winterstein and Mayer Francoz. The interrogation left the three men heavily beaten and covered in blood. Commander Senić participated in the beatings.

Twenty-two Šidian Jews were able to flee the town and find at least a temporary refuge from Ustaša persecution. The great majority of the community, however, remained in town. By summer 1942, they included five or six Jewish children from Osijek and Sarajevo, whose parents had already been deported. Anticipating deportation and desperate to avoid it, the Jewish community proposed a sort of a self-deportation plan to local Ustaša authorities, offering to collectively move to a small ranch belonging to Leopold Schlesinger, which would be turned into a guarded camp and where Šidian Jews would remain indefinitely, supported by small, self-sufficient agriculture. Ustaša authorities rejected the proposal.

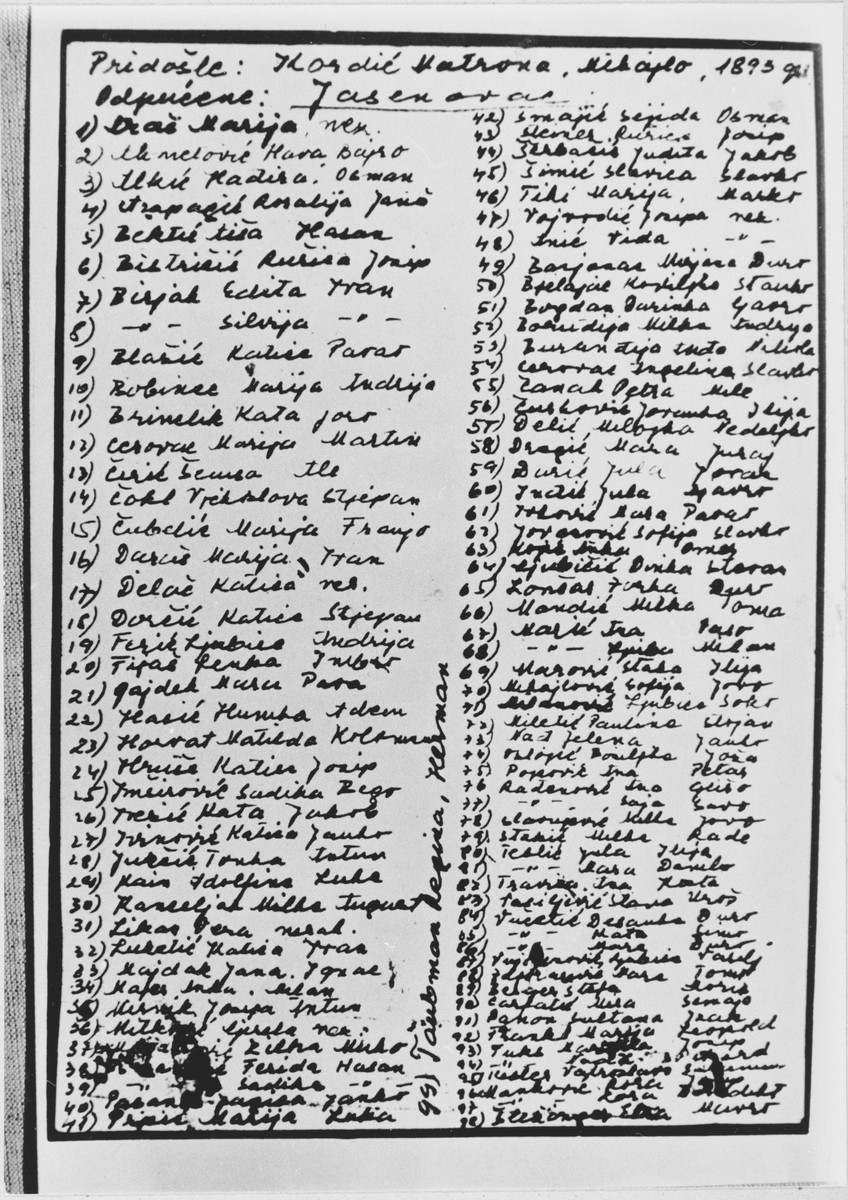

Instead, Šid’s Jews and Roma were deported in one swoop, on July 26-27, 1942. District Clerk Ivan Daražac received deportation orders for both Jews and Roma on the evening of July 26. Daražac carried out the orders that very night, personally overseeing the action. Šid’s police, likely with the assistance of local Ustaša and Deutsche Mannschaft units, commanded the Jews and Roma to pack up and mustered them in the town hall yard. There, they remained waiting until late afternoon of June 27, when the authorities marched them to the railway station, forced them into boxcars, and deported them west toward the city of Vinkovci. The same train deported also the Jews of the town of Ilok, a much larger community, which was brought to Šid with trucks and forced into additional boxcars.

In Vinkovci, Ustašas brought more than a thousand Jews to the makeshift concentration camp at the Cibalija soccer field, including entire communities from Šid, Ilok, Županja, Sremska Mitrovica, Ruma, Stara Pazova, Bijeljina, and Vukovar. They were held there for a month, living under open skies, with minimal food and makeshift hygienic facilities. Throughout that period, Jewish men, women, and girls were assigned to forced labor squads and performed heavy work around the city.

In late August 1941—most likely August 20—camp authorities ordered the Jews to pack their belongings. It was nighttime when Ustaša soldiers marched them to the railway station, forcing fifty people into each boxcar. Among all the Cibalija internees, around forty people received stays of deportation on account of “Aryan” spouses or family members serving in Croatian Home Guard units, mostly as medical workers. The rest were deported, mainly to Auschwitz, but also Jasenovac death camp, including all but four Šidian Jews. None of the deportees survived.

With this action, the Jewish community of Šid was destroyed. Only six Jews were left in the town.

One was a child, Kalmi Levy, whom local poultry farmer Bogdan Jovanović, a Serb, hid from

deportation; after Jovanović met his end at Ustaša hands, his family cared for Kalmi until liberation;

in the decades after the war, Yad Vashem recognized the Jovanović family as Righteous among the Nations.

The other five were Abram Kišicky with his wife and three children, who were allowed to return to

Šid from Cibalija because Mr. Kišicky’s brother had been drafted as a medical doctor to the Croatian

Home Guard. Miraculously, the Kišicky family was left untouched until liberation,

ostensibly because local Ustašas never learned that Mr. Kišicky’s brother eventually fled

from the Home Guard and joined the Partisan rebellion.

A total of twenty-eight or twenty-nine Šidian Jews survived the Holocaust.

Around ten of them returned to the town immediately after the war and tried to rebuild their lives,

but the community was never reestablished. None of the deported Roma ever returned to Šid.